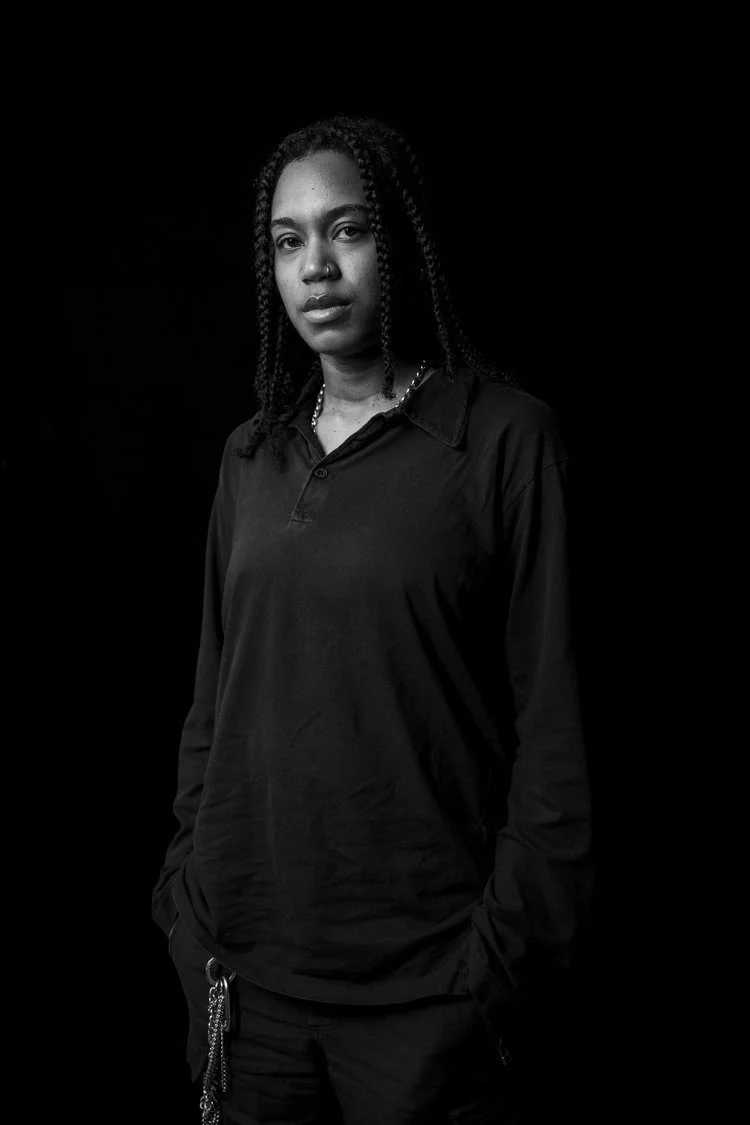

Sidony O’Neal talks to Phillip Edward Spradley

Portrait of Sidony O’Neal. Courtesy of the artist

Sidony O’Neal is a conceptual artist whose work draws from the deep logics of mathematics, architectural systems, and the mutable histories of objects. Working at the intersection of formal reasoning, synthetic computation, and embodied abstraction, O’Neal constructs processual frameworks that function as both critique and proposition. Their works do not resolve into stable forms but instead unfold across recursive tensions, where algebraic structures are held in conversation with personal poetics, and where systems—stripped of their legibility—are made to stutter, loop, or glitch.

O’Neal’s output across installation, performance, text, and digital media emerges from a commitment to the provisional: systems are understood not as fixed architectures but as mutable interfaces between language, material, and perception. Drawing on the epistemological residues of translation, symbolic logic, and software aesthetics, O’neal stages environments in which formal rigor and affective indeterminacy coexist. Their works often trouble the perceived transparency of interface, interrogating how objects behave as communicative agents, how data flows are shaped by aesthetic ideology, and how access itself becomes an aesthetic condition.

At the core of their methodology is a synthetics of form, where meaning arises not from coherence but from collisions and discontinuities. O’Neal’s sculptural and text-based arrangements evoke a language of structural abstraction: spline, grid, joint, fold. These architectural and computational fragments are not merely visual motifs but conceptual tools—markers of a logic in flux, a rhythm built from fracture. Their work resists the stabilizing impulses of genre or lineage and instead generates new configurations through latency, indeterminacy, and systemic recursion.

Their philosophical orientation is rooted in an expansive matrix that includes algebraic topology, cybernetics, and Black radical theory. O’Neal does not illustrate these concepts but instead operationalizes them. In doing so, they create spaces in which abstract ideas—computation, knowledge, ancestry, structure—are felt as material and affective forces. O’Neal’s recent exhibitions include Third Born, Mexico City; Portland Institute for Contemporary Art; Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts; SculptureCenter, New York; and Kunstverein Düsseldorf. Their recent commission by the Whitney Museum for INFANT’s, a collaboration with artist Bogosi Sekhukhuni, titled (BANNED SKILLS)—a digital work developed for the Artport platform—continues this interrogation of materiality, protocol, and access. O’Neal’s work should be understood not as final display but as durational proposition. Each project maps a conceptual architecture, inviting viewers to track the behavior of ideas in space.

O’Neal’s current exhibition, Continuous Dimensional Thorax, presented with artist Timothy Yanick Hunter at Third Born in Mexico City, is on view through July 26, 2025.

Bosses, 2024. Inkjet, heat sink, gampi, artist mat, spalted albizia frame, 31 × 24 × 1.5 in. Courtesy of THIRD BORN & The Artist.

Phillip Edward Spradley: Your work consistently engages with the languages of mathematics and systems theory, often incorporating architectural and computational structures into your visual language. How do you approach mathematics not just as a conceptual tool, but as an affective or material sensibility in your practice?

Sidony O’Neal: I have two routes out of that question. One is, intuition is very important, and every chance I get, I try to bring up intuition as it exists as something that is super familiar to people who study and work in the realm of art and literature and that kind of space, but it's also deeply, secretly deeply important to mathematicians. Mathematicians will actually talk about what it means to build intuition, as though it’s a muscle, before even approaching a problem. The space that the problem exists in, you have to build an intuition around before you can even approach or unpack or unfold the problem itself.

I feel like a large part of what I do, is synthesizing with a sense of intuition, building intuition for my practice. Which is to say that it takes a bit of time. It takes a bit of work. It sometimes takes the body of work itself to build that intuition.

Part of my approach to that is to keep working through a few different veins, some of the veins you mentioned, and I guess the other route out is that I firmly believe that if you are working in a way that's interdisciplinary, anti-disciplinary, all of these ways that confound discipline or confound lanes, and you don’t desire to be alone in that work, then you have to be so organised and sharp. If you work interdisciplinarily, you do twice or three times the research. If I’m at conferences where there are number theorists who don't know much at all about the history of conceptual art, then I’m also in places where I'm speaking to artists, curators, and museum professionals about concepts that they may be unfamiliar with or that they probably haven't reviewed in a long time.

For me, it's important to try to be a sharp communicator, and I think that that partly just comes down to organisation, or like capacity. You really have to hold it. You can't fake it. It's one of those things where you just can't fake having done or lived the work. Research is itself is a material.

a secret is not a substance (hyperbolic settee), 2024, Aluminum, fruity leather, micro suede, EPS foam, 24 x 54 x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist

a secret is not a substance (hyperbolic settee) (detail), 2024. Aluminum, fruity leather, micro suede, EPS foam, 24 x 54 x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist

a secret is not a substance (hyperbolic settee) (detail), 2024. Aluminum, fruity leather, micro suede, EPS foam, 24 x 54 x 30 in. Detail. Courtesy of the artist

Translation—linguistic, symbolic, or computational—appears as a recurring structure in your work. What draws you to the instability of translation as both subject and method?

Translation as a mathematical transformation is kind of an unattainable ideal of it’s invocation elsewhere.

I think that there's historically been a shroud over the tools, people, and entities that manage the task of translation or the space of translation. I became very interested in that when I was in high school—how there was this world of comparative literature that had had a ceremonial death in the late 90s, a breaking down around what was called “world literature” and this type of thing. I think being in the States, being based in the States, I am super aware of how little literature in translation we receive on a popular level—like do you know who the major translators of literature coming from Spanish or French language writers based in the Americas or in Africa or in Europe are? It’s amazing that there’s a countable group of people and publishers who are the arbiters and inheritors of a given translation route. It’s important to know and unpack the task and possibility in that work.

I started to think about those politics and what it is to be part of a project of translation, and to be a product of translation myself. I was translating works as a way to get closer to certain literatures. I think that brought me closer to an understanding of the systems and structures and epistemological layers that I could then name more explicitly through the work that I was doing. I still make translations inside and alongside projects.

I was in a group show at the Sculpture Center in 2020 where I presented a collection of poems written by a Mauritian poet and translator, Édouard Maunick. I had been doing a lot of research around table top games and necropolitics, and this collection of quatrains I translated from French and Mauritian Creole as “50 Quatrains to Evade Death.” I offered them alongside a sculpture as a kind of game manual for the work. It was special because there wasn't an existing English translation. So, the Sculpture Center allowed 300 copies of this bootleg translation to exist as a part of the show. Maunick actually passed away a year later, in his late 80s.

all consequence, no ground, 2024, kiss cut vinyl, aluminum, 38 x 58 in. Courtesy of the artist

You’ve described your process as research-driven, but also grounded in intuition. Can you describe what a typical research phase looks like for you? How do these modes—research and intuition—converge or diverge toward materialization?

It's not always easy to tell whether or not research has a material, or can materialise, and for that reason, there are projects that are just ongoing and will remain that way.

Then there are projects where there's no more language, there's no more appetite for research, there's no more archives. There's just an object, and it has material, and it has a form, and maybe there's even an invitation, which is always nice, and that’s sort of how things come together.

I think—yeah—to say that there's a typical formula would be really simplifying how things work for me. I actually do not like making things if I feel I already know the answer. If something pops out as a completed idea, from material to thing (in cognitive abstraction), I'm actually pretty stubborn about resisting that. I think that the bulk of my work is actually trying to find the places where research or context doesn't easily beg an object, a method, or a gesture, and working from there on what’s next.

the crowd is gauche, but the swam is elegant, 2025. Inkjet and thermopaste on uda gami, spalted albizia frame. 6. x 13 in. Courtesy of THIRD BORN and the artist

INFANT, the design entity you co-founded, seems to operate in a liminal space between design, performance, and critical infrastructure. How does your work through INFANT differ from, or inform, your broader conceptual practice?

INFANT is based in a desire to explore in ways that maybe artists with research-based practices aren't always invited to explore. Sometimes our inquiries are rather plaintiff design and architecture inquires. There were so many functional objects on our minds when we first began.

So we attempted to build and work from this place of “INFANT as a thing without or before speech", this place where our growing design language could exist alongside the knowledge and the context of our individual practices.

We are obsessed with the status of science in architecture and design, and some of that has been nice to develop and ask questions about. To varying degrees we've been successful in having our collaboration being considered as INFANT a design entity, versus collaborating artists. Although our solo practices feel different from INFANT.

We have a project with The Whitney that is coming out this summer that names and presents a very specific cultural concept that we are proposing. We've been interested in the construction of alterity, as it just keeps showing up as different seemingly unrelated “trends” throughout media and art history. Trend forecasting and the history of trend forecasting are big in the brand and marketing world, and our reflection on the ways that the production of difference through art history and media has plugged into some formal languages of artistic practice has critically taken up that forecasting register as well.

It is ultimately one of those projects that exceeds the platform that it will live on. It is an interactive environment that is meant to ask more questions, made to go elsewhere, and we've actually been working on the larger project around it for five years. We’re quite theory focused about it.

Lemmmmmma, 2023. Canon G7000, pencil on gampi, albizia artist’s frame, Drawing dims: 8.5 x 12.5 in Frame dims: 11 x 16.5 in. Courtesy of the artist

Lemmmmmmmma, 2023, Canon G7000, heat sink, albizia artist’s frame, Drawing dims: 8.5 x 12.5 in, Frame dims: 11 x 16.5 in. Courtesy of the artist

Your work often resists closure. Sculptures, texts, and interfaces appear suspended in a state of becoming. What is the role of opacity or refusal in your work? How do you imagine the viewer’s experience within that framework?

As someone who works within and outside of archives that are Canonised, my responsibility—and the politics of citation that I've developed for my work—is absolutely to confound a sense of completeness that an archivist or a single canon or discipline with certain institutional obligations might want to give. That's not why I'm in an archive. I'm not there to reify completeness or direction. I'm not in a collection to continue the illusion that everyone agrees on an experience or value for an object.

I'm certainly excited by projects that are about expanding and allowing plurality for bodies of knowledge or restructuring bodies of knowledge, and I think viewers get into that too. I think that whatever that sense of what we might call undone, incomplete, or just ceasing to close the door on some gesture is for me about the fact that there’s life, theres always other vital work—and being!—involved in or alongside a project, and not all of that is explicitly art work. Some witnesses to my work will experience and integrate this point with ease and others wont. It wouldn’t be far off to say that I make work such that no one ever has to make small talk with me.

le nid, 2021. Titanium, carrara marble, epoxy grout, acrylic, thermoplastic rubber, 2.5 x 23 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist

Program for fireback with sacrificial anode, 2023. Pallet, aluminium, steel, printed inconel, vapor smoothed TPU-70A, 34 x 30 x 9 in. Courtesy of the artist

You move fluidly between mediums—digital systems, physical installations, sculptural fragments, live performance. How do you determine the appropriate platform or medium for a given body of research or inquiry?

The stuff of my solo practice can range but is also fluid in the sense that I consider what I consider to be an object, and that’s expanded by my interest in math and computational systems, which also engage objects. For now I’m pretty allergic to painting.

Most of the research that excites me, most of the ways of working that excite me, invoke material histories. Weird routes in and out of all the objecthoods. I love industrial culture, and histories of industrial culture. Whatever I'm working on is going to touch those things.

I don't really think too much in terms of is this an installation, a sculpture, or a drawing. It's more like, what systems do I need to call upon to get to the next something, to some new knowledge about a thing. For me it almost has to feel unresolvable to begin. In the math world, it would be like, "this is an open question.” Like what are the “open questions” for my practice?

Hash Table 4 Tensors Like Us, 2023. Oiled Steel, Acrylic, 42 x 37.25 x 32 in. Courtesy of the artist

Your Whitney Artport commission, INFANT’s (BANNED SKILLS), foregrounded questions of access, permissions, and institutional interface. How do you approach or navigate working within institutional structures, particularly when the work seeks to destabilize those very frameworks?

On one hand, artists have to become pretty literate in the politics and open violence that is often present when private storage masks itself as public asset. It is sometimes an art world of large encrypting systems and their institutional avatars. I think in many cases literacy allows artists to approach these systems and structures through the people who work for them while remaining focused advocates for our work and our being. Sometimes there is genuine collaboration and meaningful resourcing. To whatever extent a project requires an institution's resources to realise something, as artists, we're always weighing—having to stay informed and agile in relation to institutional structures and the power asymmetries that maintain them.

Working with David Lisbon and Christiane Paul at the Whitney has been truly incredible, and it’s my first time working with curators on a platform where the primary investigations are web-based, interactive works. It’s been an entirely different conversation and flow for me than making sculpture or drawing or installations. I’ve definitely learned a lot about what INFANT can do, and is for, through this process.

U+220E 0, 2023. Inkjet, graphite, heat sink on uda gami, artist’s frame made of albizia Paper: 12.5 x 7.5 in Frame: 16.5 x 10 x 10.5 in. Courtesy of the artist

Many of your works feel built from fragments—snippets of language, structural nodes, broken geometries. How do you think about fragmentation as both a formal and epistemological condition? Is there a politics to fragmentation in your work?

Yes. The short and incomplete answer is yes.

I can give you an example—Some years ago I began working from an intuition that is like calculus, which is to say it is an intuition that appraises the increment. The making of differential calculus essentially relies on meaning that's derived from studying very small shifts in information, very tiny, even poetically or “infinitesimally” small shifts that can be extrapolated to understand larger changes or phenomena in a given context.

For me, what is interesting is that the time that this sort of consciousness—the time period that, for instance, calculus as a formal branch of a Western (rather than a globally practiced) mathematics was first being advanced—is at the same time that much of the world was being displaced, enslaved, and/or colonised by successive waves of European interface as settlers utilising and reifying similar differential logics. This holds for many other branches or areas of maths. We are left with an inheritance of culture and personhood that is deeply related to, if not constructed through, the endurance of trends in the production of mathematical thought.

I think that if my work feels as though it is made of fragments, then it is as close as it can be to the composite and computational systems, labour histories, structures of science, and relational logics that might shape its inquiry. However, I would rather think parts, objects, matrices, transits, and transformations than think fragments.

U+220E 1, 2023, Inkjet, graphite, heat sink on uda gami, artist’s frame made of port orford cedar Paper: 12.5 x 7.5 in Frame: 16.5 x 10 x 10.5 in. Courtesy of the artist

Looking forward, are there particular systems, histories, or speculative tools you’re interested in engaging that you haven’t yet explored in your practice?

In general I’m very excited about what artists can do with tools in a backend context. I get really irritated when certain software companies are like, “Hi do you want to test this thing that's already sealed and locked and done, and then you can put your artists' stamp of approval on it?" I'm like, "No, artists should be there for development. I want to work with the components themselves.”

I am also very interested in patent histories and the ways that legal processes complicate citation and currency in tech and science-based industries. I am looking forward to advancing an ongoing inquiry in this area as a collaboration with a mathematician who’s work I really admire.

Looking further forward, could I ever write a book?

To learn more about Sidony O’Neal visit their Instagram