Raina Lee talks to Phillip Edward Spradley

Portrait of Raina Lee. Courtesy of the artist. Photographer: Andrew Wren

Raina Lee’s ceramics exist at the threshold between artifact and apparition, offering objects that feel both unearthed from a distant past and conjured from an imagined future. Based in Los Angeles and working from a treehouse studio in the hillside neighborhood of Mount Washington, Lee engages clay as both a responsive collaborator and an unruly force. Her vessels often echo geological phenomena such as eruptions, crystallizations, and sedimentary accumulations, yet they reveal a deliberate sense of proportion, rhythm, and sculptural poise.

Rather than adhering to the symmetry and polish associated with traditional pottery, Lee cultivates surfaces that register geological time. Strata of glaze run, pool, or fissure; edges warp like eroded stone; skins blister and pucker as though transformed by heat and pressure deep within the earth. These qualities resist predictability, allowing the kiln to participate in the act of creation. Her practice becomes an alchemy of intention and accident, with each object’s final form negotiated between artist, material, and fire.

Lee’s vessels invite multiple readings. They may be understood as ritual tools, speculative relics, or narrative containers. The act of holding space—whether physical, emotional, or symbolic—is central to her approach. The interiors of her works are as resonant as their exteriors, suggesting that what a vessel contains may be intangible, such as memory, myth, or the trace of the artist’s own gesture.

Her background in zine-making, digital media, and writing informs this narrative sensibility, allowing each piece to carry meaning beyond its physical form. Through clay, she constructs not just objects but cosmologies—imagined worlds where texture, form, and surface operate as language. In this expanded field, glaze becomes a kind of script, the body of the vessel a terrain, and the work itself a site of storytelling.

Lee’s practice also offers a meditation on impermanence and transformation. By embracing entropy, including cracks, drips, and the unpredictability of chemical reactions, she acknowledges the ways in which making parallels living: both shaped by forces beyond full control. Her ceramics speak not only to craft traditions and material experimentation but also to broader questions about time, change, and the persistence of beauty within the imperfect.

Lee holds degrees in Sociology from the University of California, Davis, and in Media and Film Studies from The New School for Social Research, as well as training in Ceramics at Glendale Community College. Her work has been exhibited at galleries and institutions including Niche Gallery and Stroll Garden in Los Angeles, among others.

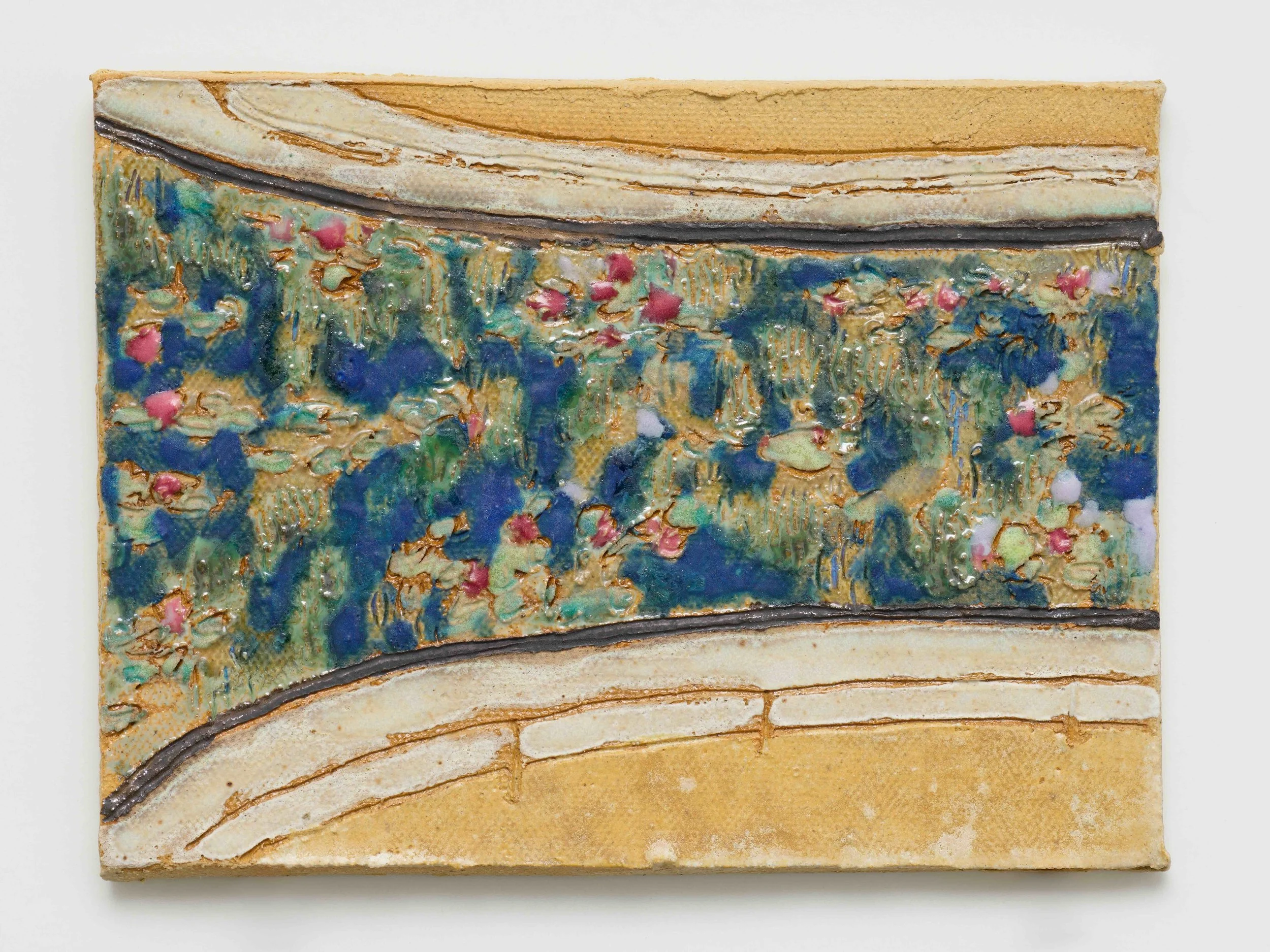

Impression Sunrise, 2025. Stoneware, glazes, 12 1/2 H x 15 W x 1 D in. Courtesy of the artist.

Phillip Edward Spradley: Given the inherent unpredictability of glaze chemistry and kiln firing, what criteria or intuitive markers guide your determination that a work is complete?

Raina Lee: It’s intuitive. If it looks done, it’s done. The main issue I have with ceramics is when I didn’t get enough glaze on a certain spot. I have to ask myself if it’s something I can live with. Otherwise, every time I re-glaze and re-fire it’s more likely to break. It’s not like painting where you can just touch it up with a little paint. If I want to re-glaze, I have to decide whether it’s worth total heartbreak and failure.

How do you conceptualize failure within your studio practice, and can you recall instances where unanticipated results catalyzed significant aesthetic or conceptual breakthroughs?

I realized early into doing ceramics that unless you just work with static underglazes (the painting equivalent is acrylics), there is always an aspect of chaos. The clay might warp, the glazes might run, weird colors might come out— all unexpected results. I figured if this was a way I wanted to express myself, I would embrace unpredictability as a fundamental working property. I am highly controlled in what materials I use, and work with glazes I’ve made myself and used for years so I can predict their behavior and material responses. I can control up to 90% and the other 10% is in the hands of the kiln god.

Waterlilies at l'Orangerie, the Blues, 2025. Stoneware, glazes, 4 1/2 H x 6 1/4 W in. Courtesy of the artist.

In your glazing and construction processes, how do you negotiate the tension between technical control and material spontaneity?

I work with the expectation of controlling 90% of the process and giving up the last 10% to the kiln. It’s freeing actually, knowing you can’t control everything. Is that what Oprah calls a teachable moment? If I had to control 100% of the outcome, I would not work in clay.

Could you discuss a recent studio experiment that deliberately challenged your established methods, materials, or conceptual framework?

Working in the format of “ceramic glaze painting" is a newer experiment for me. I’ve only been doing it since last summer. I’ve spent a few years making textures volcanic and crackled glazes, as well as refining the glaze colors I’m able to get with natural compounds— copper, iron, cobalt, titanium, chrome and nickel. I wanted to highlight the surfaces of these glazes, and on a large pot sometimes the glazes are taken for granted. I thought if I tried channeling the glaze into painting, their nuances and textures would be considered and taken more seriously. Instead of ceramic glaze being a way to decorate pots, I am interested in using glaze as way to express time and emotion.

Paris Blues Meiping (Skateboarders of Palais de Tokyo, Tour Eiffel and Parc des Buttes- Chaumont), 2024. Stoneware, underglaze, glazes, 20 H x 12 W x 12 D in. Courtesy of the artist.

Paris Blues Meiping (Skateboarders of Palais de Tokyo, Tour Eiffel and Parc des Buttes- Chaumont), 2024. Stoneware, underglaze, glazes, 20 H x 12 W x 12 D in. Courtesy of the artist.

Paris Blues Meiping (Skateboarders of Palais de Tokyo, Tour Eiffel and Parc des Buttes- Chaumont), 2024. Stoneware, underglaze, glazes, 20 H x 12 W x 12 D in. Courtesy of the artist.

Your vessels often evoke both ancient artifacts and speculative futures—how do considerations of temporality or timelessness inform your formal and material decisions?

Just as good writing references literature from the past, as well as good painting builds upon previous art, I reference works across ceramics history and art history to build a contemporary visual language. I believe we do not live in a vacuum, and our language and thoughts are the culmination of memories that are passed down. I like looking at works from China or neolithic Jomon works from Japan, as well as Persian and Greek ceramics to inform my practice as well as uncovering why these civilizations made these works. Sometimes I look at how incredible Song Dynasty glazes and shapes are and how we’ve never really surpassed them, in terms of beauty an technical ability. It’s astonishing how Song works look ultra-contemporary even today.

Delftware at Sèvres, 2024. Stoneware, glazes. 4 1/2 x 6 1/4 in. Courtesy of the artist.

When initiating a new body of work, do you typically begin from a conceptual inquiry, visual archetype, or a process-oriented engagement with material?

I start with a conceptional framework for an installation idea. From there I can quickly generate a body of work, whether it is sculpture, a series of vessels, paintings, or object installation. Though I am very materials oriented, having experimented in glass casting, paper pulp, 3D printing, and fiber, I try to figure out what materials support the idea and make the most sense. Even though I don’t have one methodology, I have noticed that I want to make work where my hand is very apparent. I often wonder if that’s a reaction to technology and AI, as a deliberate protest. I used to publish punk rock zines as a teenager and found it interesting that these publications looked like a real person made them and they were messy and flawed. I love highlighting the idea, in the format of the work, that all information comes from someone and somewhere, and that it’s subjective and messy. Even content that AI and ChatGPT generate is subjective and messy.

Foujita’s Kiki de Montparnasse, 2024, Stoneware, glazes, 9 1/2 H x 14 W x 1/2 D in. Courtesy of the artist.

Do you situate your practice in dialogue with specific artistic movements, mythologies, or cultural-historical narratives, and if so, how?

In my work I respond to moments in art history and craft history. I suppose I make work about artworks I’ve closely studied or been inspired by, as it pertain to my personal history. I’m a Taiwanese American child of immigrants who grew up in my parents pizza restaurant.

I’m also interested in the performance of the museum, and how artworks enter the canon. I’m obsessed with how museums install work, how the works got there, and what context they are creating for the work. As an undergrad I interned at the Smithsonian and have worked at a small Chinese American museum so have been interested in how institutions contextualize work and people of color.

Blue and white Chinese porcelains at Musée Guimet with Rachel, 2024. Stoneware, glazes, 4 1/2 x 6 1/4 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In what ways has your background in writing and media shaped your approach to narrative construction within the medium of clay?

My work is narrative, if it’s about engaging with the Islamic tile work at the Alhambra or wood firing and viewing Mingei crafts in Japan. I’m probably faster at articulating a narrative since I’m a professional writer.

Do you conceive of your vessels primarily as functional objects, symbolic forms, spiritual artifacts, or as occupying a liminal space among these categories?

All of the above. I am fully aware there’s a kind of classist discrimination against work that is functional, and in the art world it’s perceived as lesser. I find no shame in work that fulfills all the categories you just mentioned.

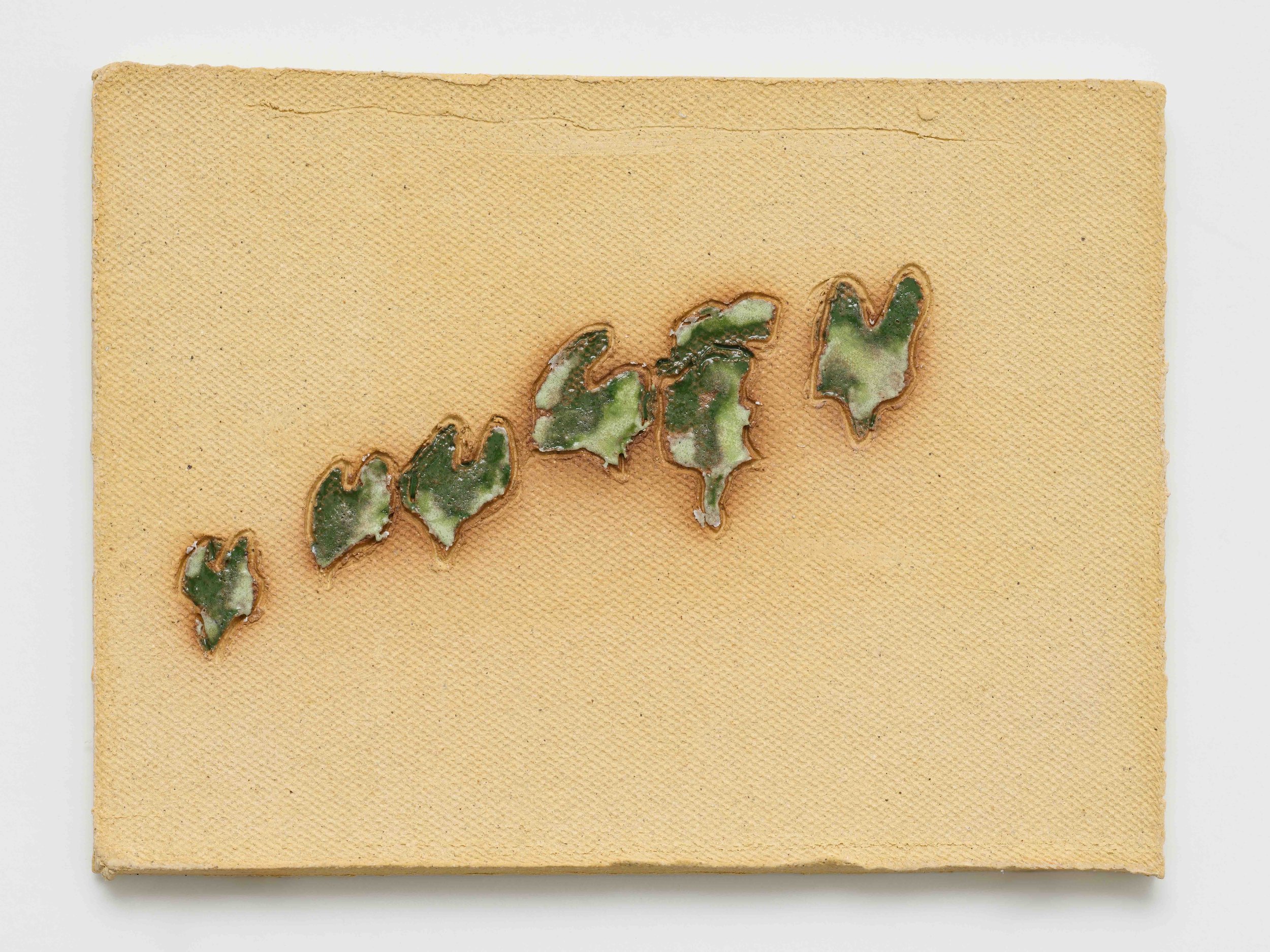

Ellsworth Kelly’s Plant Drawings at Fondation Louis Vuitton, 2025. Stoneware, glazes, 4 1/2 H x 6 1/4 W in. Courtesy of the artist.