Mary Herbert talks to Phillip Edward Spradley

Portrait of Mary Herbert. Photo by Hannah Burton. Courtesy of the artist

Mary Herbert is a London-based artist who explores the delicate, intangible spaces where consciousness, memory, and dreams converge. Working with soft pastels and oils, her art navigates an interplay of emotions, sensory experiences, and subconscious forces. Through her paintings and drawings, Herbert invites viewers into realms where perception and reality blur, and time flows in non-linear, cyclical patterns.

Herbert’s paintings are populated by images that seem to emerge from somewhere just beyond our grasp. Soft, fragile colors imbue these scenes with a sense of evanescence, evoking the mood of a distant, shared memory. For Herbert, this space defies conventional thinking. She finds inspiration in unseen moments and sensations from our reality and believes that the act of dreaming challenges the way we are conditioned to perceive reality. She views dreaming as a non-linear process that aligns with feminine, cyclical, and spiral conceptions of time—an alternative to the traditional, linear progression emphasized in much of society.

Mark-making plays a crucial role in creating this dream-like atmosphere. Blurred lines and soft edges dissolve boundaries, leaving form in a state of flux. The energy in Herbert’s work is raw and dynamic, pulsing with fragmented intensity. It resists smoothness or refinement, radiating a vibrant, unpredictable vitality. This energy, charged with tension, draws the viewer deeper into an emotional and almost hypnotic state.

Herbert earned a BA in Fine Art and Contemporary Critical Studies from Goldsmiths, University of London, before completing a Postgraduate Diploma in Drawing at The Royal Drawing School, London. Her growing recognition is evident in her exhibitions in London and abroad. She has shown her work at esteemed institutions such as Lychee One, Union Pacific, White Cube, and The British Museum in the UK, and exhibited in galleries across Europe and the US, including F2T Gallery in Milan, Moskowitz Bayse in Los Angeles, the now retired Fortnight Institute in New York, and Meyer Riegger in Berlin. Her work is part of the permanent collections of both The British Museum and The Royal Collection.

Herbert has an upcoming exhibition with Moskowitz Bayse at 223 Cambridge Heath Road, London on May 15, 2025 and runs through June 28, 2025.

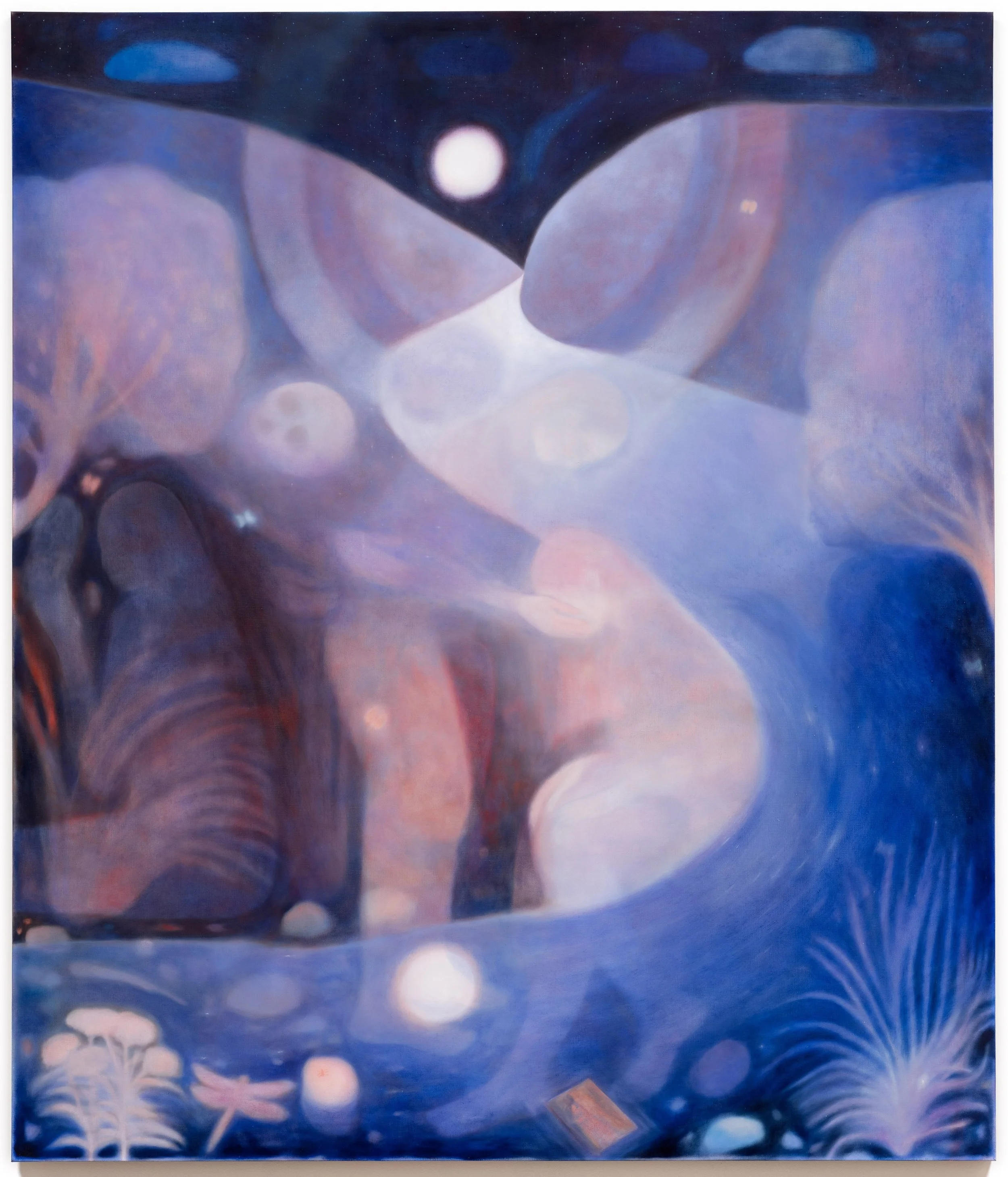

Care, 2022-23, Oil on linen, 180x200cm. Courtesy of the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, LA

Phillip Edward Spradley: Your paintings have a captivating radiance and a sense of mysticism that feel inviting, they create a space I wish I could step into. Can you talk about how you navigate these soft environments and the hazy figures that inhabit them, particularly when dealing with the intangible themes of memory and dreams?

Mary Herbert: It's a lot to do with the physical process of making the work. I was thinking recently - is it strange to make a painting that privileges the other senses that are not visual? Like bodily inner sensations or movement, or touch. Touch is really important to me, and I think I start from there.

For the past year I've been doing a contemporary dance class, and it’s really expanded the way I think about my process. I got interested in it from drawing - at the Drawing School we had these classes where we learned about Laban dance notation and applied it to drawing. The movements combined three variables; space, time and weight, in different ways. So for example you could have a quick, soft and indirect movement, or a slow, forceful and direct one. Some of those movements really resonated with me and some of them I found really jarring, and I was interested in this tension. At the time I was doing most of my drawings outside, I think because there was something about the constantly shifting and changing environment that allowed me to also touch in with what was going on inside. The dance/drawing class fused those things together - outward observation and inner observation.

I was thinking also about how to answer this question about the mystical, because I agree that I am working with this material, but I’m not entirely comfortable with the way it’s framed. People often use the words ‘ethereal’ or ‘otherworldly’ as descriptors for the work, and can absolutely see why, but I was wondering - why do I find them jarring? I think it's because I feel like they set up a binary between our everyday experience of the world and some other realm, or between what’s rational and irrational. For me the project is to dismantle this opposition in the work, so that it exists as a believable and felt space in the world.

Installation view of Soft Logic, Moskowitz Bayse, LA. Courtesy of the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, LA

You’ve spoken about the way dreams defy linear progression. How does this influence the technical aspects of your process, especially in terms of capturing a fleeting memory?

There is a kind of tidal process that seems to happen with the paintings which is not linear, things need to be able to disappear and re-enter. It’s a bit like trying to remember a dream, if you try to look at it straight on or hold on too tightly, it just disintegrates. The paintings are built up in successive layers, and I’m trying to get to a point where it feels like just enough is there, not too much or too little. It’s different for each painting. Some paintings go through many layers of painting over and repainting to get the right balance, and some happen more quickly. I’ve been trying to hone the skill of recognising when it is just enough, even though I might like to push it further.

Tether, 2022-23, Oil on linen, 150x180cm. Courtesy of the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, LA

The idea of the liminal—where boundaries dissolve—seems central to your work. How do you manage this liminality when deciding what to leave visible versus what to obscure, and how does that process reflect your engagement with the unconscious or the dream state?

Deciding what to leave visible often comes out of a process of painting things and then erasing by painting over, it’s very intuitive and feeling based, and the decisions can sometimes take a long time to realise. I think it relates back to the lapping and overlapping of time in the work. Quite often I’ll start a painting at a particular moment and wonder - what’s this and where did it come from? And then something will happen in my life and it seems to reveal itself. It’s not like I’m looking for meaning, or that I need to know it in order to finish the painting, but sometimes they kind of feel like I’ve been painting them for a moment that hasn’t happened yet, as well as touching a moment that has passed. This last autumn I was pregnant and really struggling to work in the studio through the nausea and exhaustion. There was this one painting in particular I felt kind of embarrassed by. I had been working on it for a really long time and had become almost resigned to it failing. Towards the end of the first trimester of my pregnancy I had a miscarriage, and I needed to take some time out of the studio. When I came back, I felt glad of this embarrassing painting - it was like I’d been painting it for this moment. I felt held by it and I knew how to finish it, I knew I could just let it be what it was. I think states of grief are often strangely where we feel things as most alive and connected, and there is something about trying to reach this place in the paintings. On a good day I'll be able to trust that whatever is coming up is meant to be there. Half the work feels like it's about paying attention, and the other half about finding the trust in the process.

Installation view of Soft Logic, Moskowitz Bayse, LA. Courtesy of the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, LA

Your works often appear fluid and in a state of transformation. How do you approach mark-making in your process, and do you see your mark-making as an attempt to capture a specific moment in time or more of a reflection of the non-linearity of human experience?

Touch is really present and important in my work, and I think mark making is a way of communicating touch in painting. When I go and look at paintings in museums I find it amazing how this touch reaches across time, sometimes it really feels like you’re standing in the room with the person who made the painting. The technology hasn’t changed much - little bits of brush fibre, drips of paint, a dab or a scratch or a scumble are all traces of the body of the painter and it feels very alive regardless of when the painting was made.

Mark making is very intuitive for me once I’m actually painting. I see it as quite a musical or vibrational thing, but there’s also the kind of mark making where you’re attempting to draw something specific, and the failure in this is interesting to me too.

I have been increasingly starting paintings by thinking about a gesture or a kind of rhythm that sits underneath everything. For example it could be a wavelike rhythm, a tight grid over a stain, or more frenetic layering of marks. Slowly images occur from these. I do sometimes have an idea of an image in my head at the beginning but I find I need to be able to let it go completely, and sometimes the image gets entirely buried in this process in order to make way for something else. It's about holding on really lightly to everything. This year with this body of work, I've been feeling like this process is ridiculous because there's nothing to hold onto. It's like you're starting somewhere and then things are not clear for a really long time and there's a chance they might never be and it might fail. It's kind of like that I think!

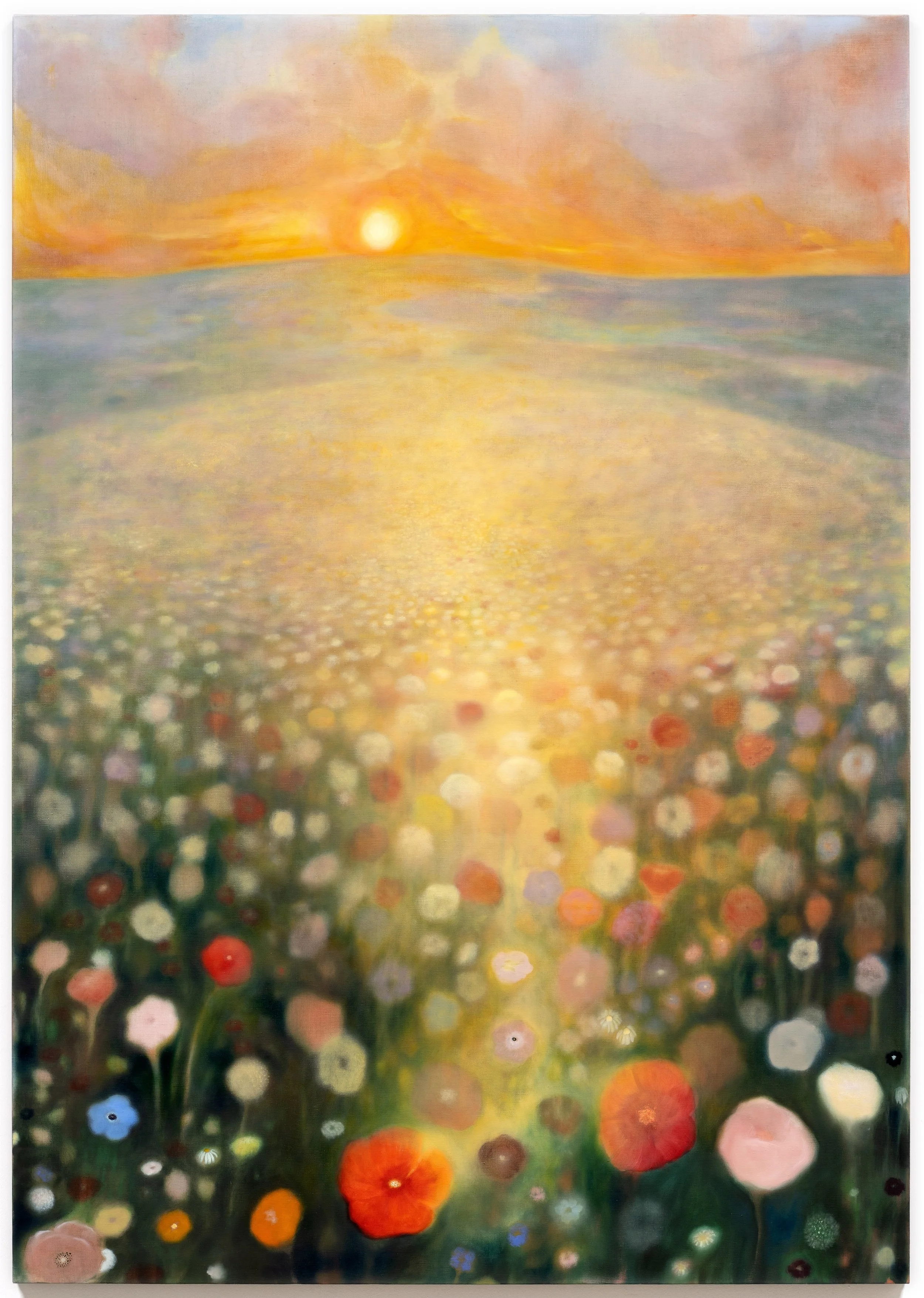

Wildflowers, 2023, Oil on linen, 120x170cm. Courtesy of the artist and Moskowitz Bayse, LA

When crafting your paintings, you navigate through a series of iterations, each layer building upon the last. How do you decide when a painting is complete, and how do the successive layers contribute to the creation of a space that feels both dreamlike and tangible?

The short answer is that it's really difficult. I don't know. Each painting brings up its own questions about where it should be left. I photograph each session I work on a painting, and then store them in a folder in date order so I can look back on various stages. Sometimes I’ll realise there was more in it a few stages ago, so I’ll think - what can I do to move forward with the energy from that previous layer?

I think letting them finish where they do is usually a kind of energetic decision. Asking - do they feel alive or not? Sometimes it can take a while to work that out. I find putting them away for a while helps, and sometimes it takes someone else’s eyes to see that they are finished. Friends and peers are invaluable when it comes to seeing what the painting is doing, when you’ve looked at it too much and can’t see it yourself anymore.

Given the spectral and sometimes ephemeral nature of your figures, how do you navigate the tension between the fragility of your materials and your desire to create a vivid, visceral presence within the work?

I don’t really see these things as being in tension, I think a fragile and fragmented thing can have just as much vivid and visceral presence as a robust thing. I have grappled with wanting to have a space that you feel like you can walk into, a kind of believable space, but also letting go of any kind of rules - perspectival rules, or rules about light and tone. I have tried in the past to work within these structures, but it often ends up feeling forced and I get into a tangle of trying to make things ‘correct’. In the end, the sense of presence has to come from somewhere else, and it’s still a bit mysterious to me what this is, although I know a big part of the equation is colour.

Seconds, 2023-24, Oil on linen, 170x80cm. Courtesy of the artist and F2T Gallery, Milan

You’ve described a connection between dreaming and cyclical, feminine conceptions of time. Could you elaborate on how you view the relationship between your use of visual symbolism (such as moons, pools, flowers, and trees) and these cyclical models of time? How does this challenge or expand traditional representations of temporality in art?

As well as the imagery in the work, time seems to manifest through composition: direction, movement and rhythm. Again, these things don’t really feel within my control a lot of the time. Once a few paintings have built up I can start to see a pattern or an impulse towards a certain structure. In the last body of work, it felt like there was a spiral rhythm running through all of it. The middles of the paintings seemed to have this kind of magnetic pull and everything responded to this. In almost all of the paintings there were shapes that could be a sun, moon or star. In this current body of work everything is a lot more linear - diagonals and horizontals are cutting up the space, and there are hardly any visible horizons or indications of cyclical time like the sun or moon. The rhythm is more jagged, space and time in the work feels a bit more collapsed.

I think the spiral rhythm in the last body of work came out of Covid, which felt like it kind of cut through the veil of capitalist time. It was easier to pay attention to this more cyclical time because things were forced to stop or slow down and everything was up in the air. I feel like this new body of work is grappling with this moment in time we are in now, and how overwhelming it feels. It hasn’t felt right to have too many clear markers of cyclical time, maybe because it just feels obscured by anxiety, or something that feels more horizonless. The paintings really feel like a way of digesting and being able to see these things, of making them more tangible and potentially having some way to feel them collectively. I don’t set out by thinking directly about these things, but they enter into the work via a kind of necessity.

In terms of the recurring motifs, like flowers, water, sun and moon, it’s partly what I’m paying attention to on a daily basis, and those are often the things that speak to this more seasonal or cyclical experience of time. There’s also something about the ability of these things to go beyond the symbolic into specificity, gesture and slippage of meaning. I don’t think I’ve managed it yet, but maybe in this body of work I’m getting closer to being able to paint these things without them staying only in the realm of the symbolic. I’m interested in what happens in painting and poetry when familiar things are made strange.

Family, 2021, Soft pastel on paper, 38x28.1cm. Courtesy of the artist

Your landscapes often feature dissolving bodies and shifting forms that seem to emerge from or dissolve into the environment. How do these figures challenge traditional representations of the human form?

I have always had an impulse to fragment the figure, and maybe it’s because I’m trying to get at what it feels like to be in a body, rather than what it looks like, or to describe any kind of character or narrative. I think this impulse to fragment the body also comes from lived experience of both the fragility and incredible resilience of bodies. I see the term ‘bodies’ as expansive and permeable, including the non-human. Perhaps because of this, I don’t see the ground of the painting as a backdrop for the human form - I want each part of the painting to feel as alive as the other, so boundaries between figure and ground are by nature more permeable.

Gesture is also important, sometimes all that’s needed is a hand or a foot placed in a certain way or in relation to something else, and any more information about the figure obscures the sensation that is coming through. I think it goes back to this idea about dissolving the opposition between what is rational or provable, and what is sensed, felt and experienced. I recently heard an interview with the philosopher Timothy Morton which resonated with this - he said ‘This ‘feelings vs ideas’ duality is a fake duality. I would suggest that it’s part of this whole subject vs object, active vs passive, also master vs slave, which is the main template that’s screwing everything else up’.

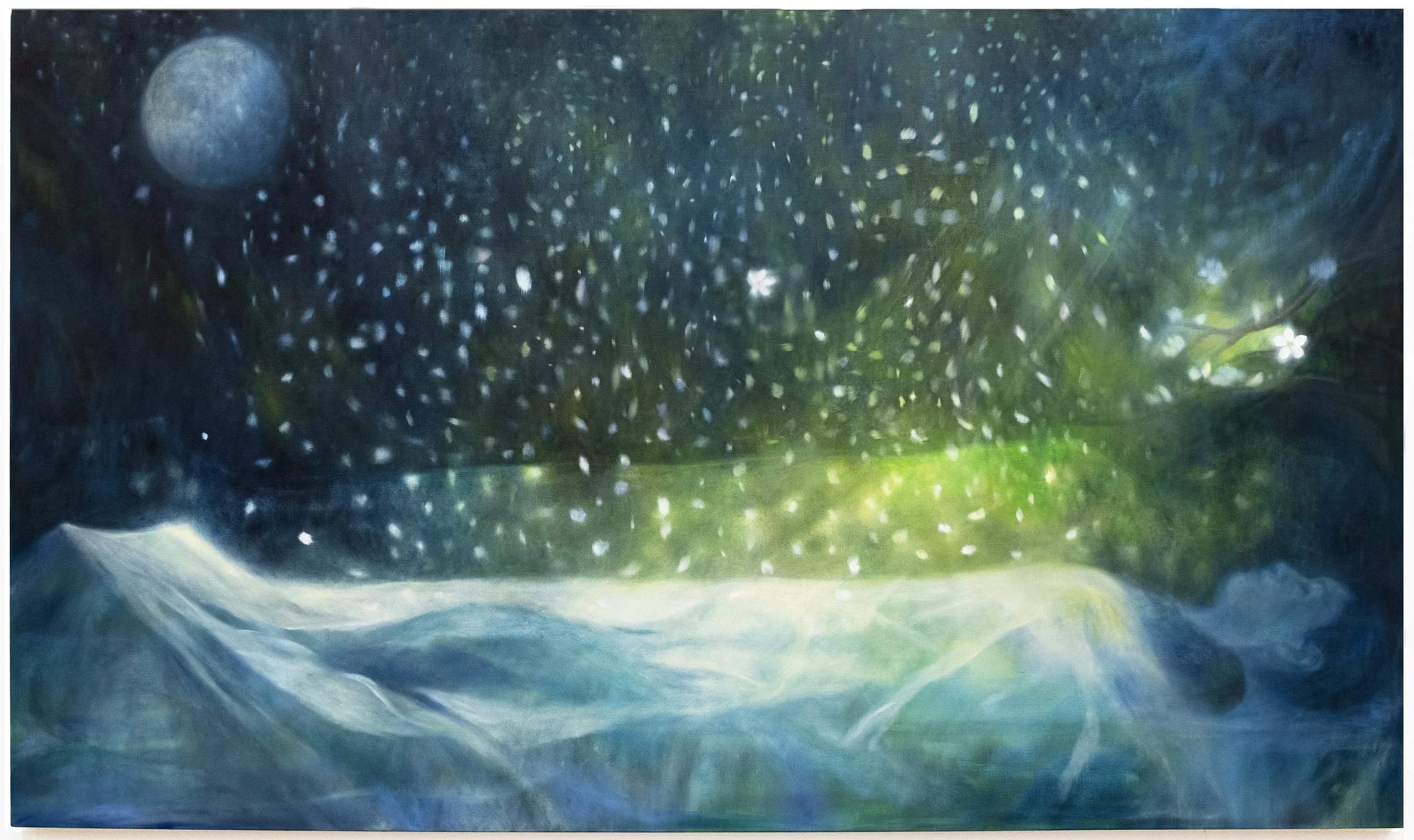

Look Between the Rain, 2023, Oil on linen, 120x200cm. Photography: Theo Christelis. Courtesy of the artist and White Cube, London

Your work has been called surreal and emotionally engaging. Do you see your environments as reflections of alternate realities or as symbols of the mind’s inner workings?

I see the paintings as doorways or portals rather than pictures, which implies a kind of active space, it requires you to come towards it as much as it comes towards you. I think in this way the work is really felt in the space between the work and the person or people looking at it. It’s a bit like how I see music or poetry, it’s not just about comprehending meaning within the material, but there’s something felt that is different each time we encounter it, and it’s really hard to talk about it because it doesn’t stay still.

What can visitors expect to see in your new series of work with Moskowitz Bayse in London?

The exhibition will be in a beautiful light space on Cambridge Heath Road, adjacent to Rose Easton. I have been working on this body of work for over a year, so it feels like there has been an evolution in the painted language since the previous show in 2023. I have made a series of paintings that are body-scale - a similar height to me or a little taller, and there will be a series of small works on paper which are more intimate in scale. In the previous body of work, the palette was underpinned by blues and violets, and in this body of work there are more earth tones, greens and green leaning blues. The surfaces of the paintings are made up of more conflicting rhythmic layers, and the sense of light has shifted, with more close tones and values, some paintings remaining very dark and others very light. I’m also really excited about a commissioned text by Aisha Farr, who wrote the text for the last show. This time it’s a more expanded piece of experimental fiction called ‘Everything-But Green’. It feels like a whole other space has been opened out between the text and the paintings, and it’s been a gift to collaborate with her again.

Sea Change, 2023, Oil on linen, 41x36cm. Courtesy of the artist and Union Pacific, London

To learn more about Mary Herbert, follow her on Instagram and visit her website at mary-herbert.com