Kelly Wall talks to Phillip Edward Spradley

Portrait of Kelly Wall. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Lili Peper.

Los Angeles is a city where meaning often hides in plain sight, it’s tucked into sun-faded storefronts, souvenir kiosks, and the kinds of objects made to capture moments that never quite stay still. It’s within this landscape of manufactured memory that sculptor Kelly Wall’s sensibility formed. Her work grows from a lifelong curiosity about the items that sit at the edges of experience: souvenirs, props, tchotchkes, and the display systems that quietly shape how we understand place and remembrance. Over time, she has turned this attentiveness into a practice that is materially exacting yet conceptually open, examining how we commemorate, idealize, and mythologize what always seems on the verge of slipping away.

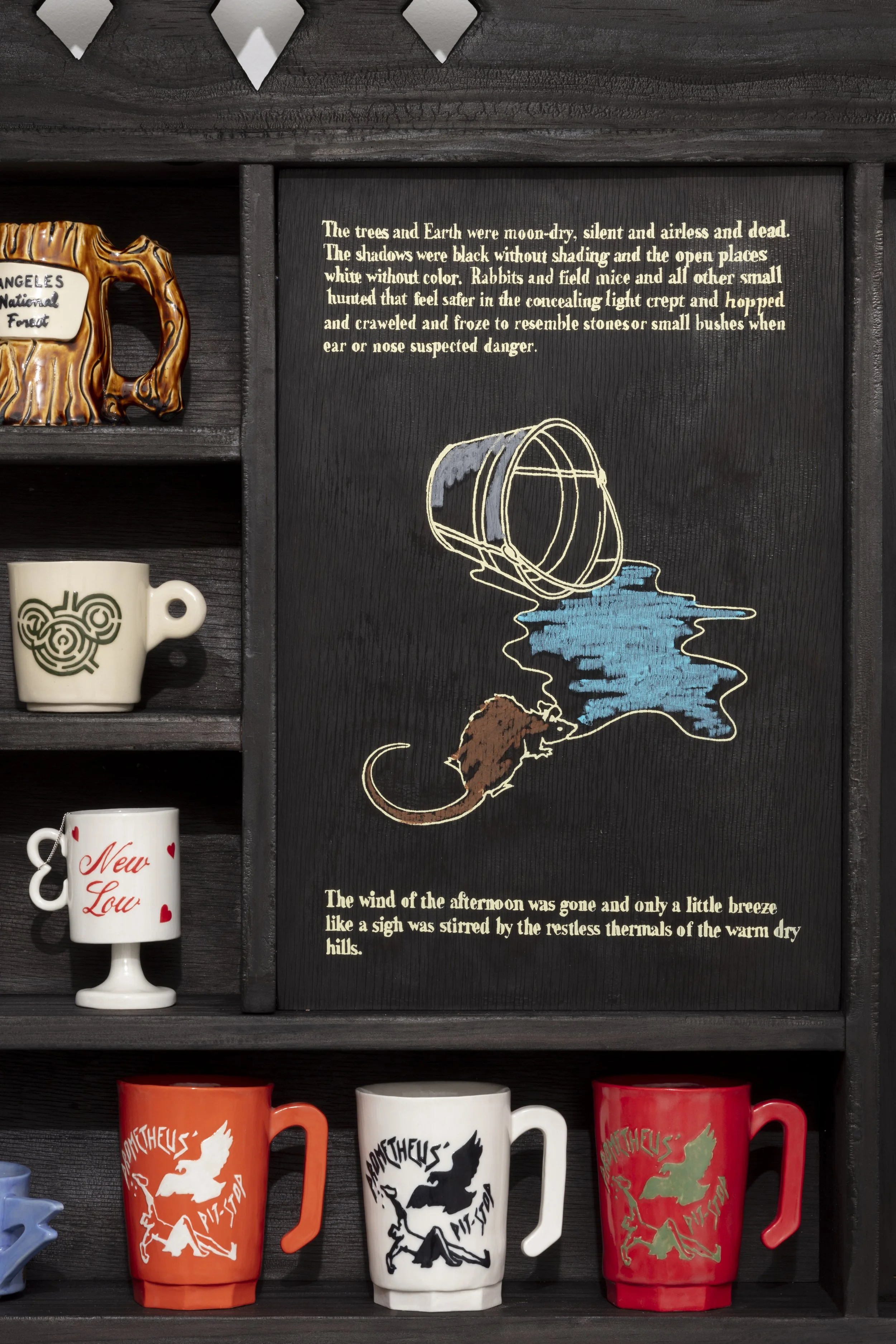

Wall’s recent projects, often circling around devotion and storytelling, push this inquiry into the rituals of sentimentality. Instead of sacred scenes, she gives everyday objects a kind of careful, almost reverent focus. The outline of an ashtray, the frame of a folding beach chair, or the balancing act of stacked souvenir mugs become spaces where trompe-l’œil works as a gentle visual disruption. It nudges our perception just enough to make us question what’s real and what’s staged. Familiar things take on a new strangeness, detached from their practical use and reassembled as markers of feeling.

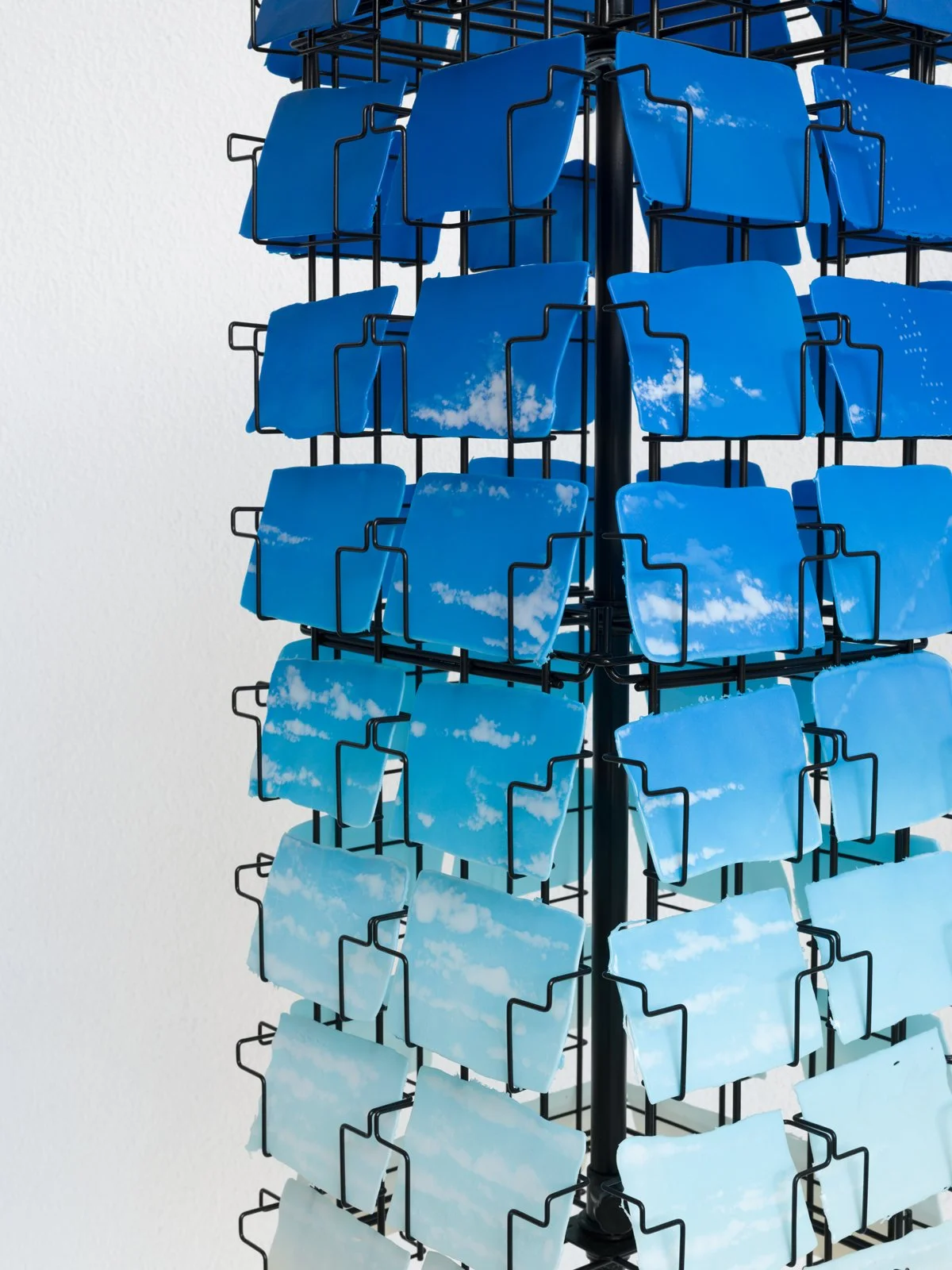

Her engagement with display systems introduces a similar kind of tension. She takes the infrastructures built to package memory—postcard racks, coin presses, retail fixtures—and reimagines them as forms that resist easy reading. Wall’s use of glass, inspired by the elusive gradients of the Los Angeles sky, and tokens stamped with ambiguous cues rely on near-illusionistic shifts in surface and material, softening the commercial promise of clarity and certainty.

Running through all of this is Wall’s steady attention to the unstable sense of “here,” a condition Los Angeles continually complicates. In a city that sells place as spectacle while confronting environmental precarity, her sculptures register the dissonance between presence and disappearance. They reflect a landscape where memory is constantly being produced and eroded—where belonging often hinges on objects that promise permanence but can never truly hold it.

Wall earned her BFA from Otis College of Art and Design and her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts. She has exhibited at institutions and galleries including Various Small Fires, New Low, OCHI, François Ghebaly, The Hole, Noon Projects, Pio Pico, and the Aspen Art Museum. Her work is currently featured in Made in L.A. at the Hammer Museum, on view through March 1, 2026.

Something to Write Home About (#1-4), 2025. Powdered glass, postcard display rack. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Jeff McLane

Phillip Edward Spradley: Los Angeles appears throughout your work as more than a backdrop. It functions as a subject with its own contradictions and mythologies. How has growing up in this city shaped your thinking about place, memory, and the aesthetics of longing?

Kelly Wall: Growing up in LA has had a huge influence on my work, often deriving from the tropes of the city: Hollywood and the movie industry, the perma summer and beach, the flat sprawl, and the unseen pull that calls people to move here. It’s funny being from LA because the moment you turn 18 and meet new people suddenly, you’re told that “nobody is from LA” and that’s something I’ve spent a lot time thinking about. When your hometown is a destination that thousands of people seek out, you start to really look at everything anew. Living somewhere that could at one moment be the setting for 100 different locations or times gives this place a heightened sense of potential, the idea that LA is where ‘dreams come true’, storytelling felt a part of the city. I think in that way Hollywood played a big part in the narratives I insert in my work, that the lines between what’s fake and real are blurred. I’m often trying to understand what makes a place, what drives that unseen pull, or longing, that draws so many here, through its buildings, industries, histories, people and ya mythologies and lore of the city.

Something to Write Home About (#1-4), 2025. Powdered glass, postcard display rack. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Jeff McLane

Your work often elevates everyday objects tied to tourism, nostalgia, or domestic life. When you begin a new project, what is it about a particular object that first captures your attention?

I’m drawn to a lot of what I would call ‘lived objects’, things that generally are used or from a nearly by-gone time, objects that feel like they have their own history or storied past but are mundane and easy to overlook because of their commonality. I think these things are ripe for play in my work since, being a mass-produced object, many people can look at them and have their own associations and memories that they can project onto the pieces. I think their familiarity and generic-ness leaves a lot of space for the viewer to enter, and I like the idea that the viewer is the final element in my art. I like to think that their associations and memories are in a sort of back and forth dialogue with the work as they look at and experience a sculpture or installation.

Wistful Thinking, 2025. Penny press, fiberglass, resin, foam, paint, epoxy, wood, vinyl. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Jeff McLane

Wistful Thinking, 2025. Penny press, fiberglass, resin, foam, paint, epoxy, wood, vinyl. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Jeff McLane

Many of the objects you choose to reimagine are inexpensive, mass-produced, and easily overlooked. By remaking them with meticulous craft and unexpected materials, you alter their emotional and cultural weight. Do you see your sculptures as offering viewers an alternative way of engaging with memory, or are they more concerned with acknowledging the limits of preservation?

I’m interested in viewers reexamining their understanding and perspective on the world, and I think that shift starts through reexamining memory. Using common place ‘lived objects’ to instigate that shift feels like a covert and subtle way in but what I’ve tried to focus on initially is the sentimentality an object provokes in me and then work back from there.

When I first got into sculpture in undergrad I was hooked by assemblage but struggled to make work from the objects I had collected. The objects felt “done” already and that anything I did to them would ruin it. At some point walking through a secondhand store I started thinking “What is it about this mug that is so appealing to me? Why does this totally average object tug at my heart?”. That’s when I started exploring recreating objects, I wanted to see if it was possible to manufacture nostalgia. By meticulously making something it enters the trompe l’oeil arena where, at an initial glance, it still inhabits the original form. By changing the material, slightly altering the shape, or including tropes, text, or imagery that wouldn’t necessarily be in the original, I’m hoping to cause a double take experience; To have the invested viewer reexamine something they thought they understood, and I think that reexamination is inherently an engagement with memory.

Beside Myself, 2023. Glass, lead, aluminum. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Evan Walsh

Fool's Paradise, 2023. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Evan Walsh

Your practice moves between the discipline of studio craft and the concerns of conceptual inquiry. The technical demands of fabrication, especially with stained glass, require patience and precision, while your subject matter engages questions about memory, desire, and cultural language. How do you balance these modes of working?

I try and navigate the balance between concept and form by continually coming back to the materials or objects I’m working with and thinking through their associations, often asking the question ‘what does that make me think of?”. So, when I’m starting a new work, whether its beginning with an object or material, I’ll ask myself this question and work from there. What are my associations and how can I use what’s inherently there to create a narrative for the viewer to explore? Material and form have an amazing ability to carry meaning and by returning to this question my hope is that my finished work holds all the concepts I’m exploring via the material I selected, how it was manipulated, the context and installation of the pieces etc. sort of like a visual poem of associations.

Hanging Over Me, 2023. Glass, lead, aluminum, steel. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Evan Walsh

Glass has become a defining material in your practice, carrying historical and spiritual associations. What led you to adopt this medium for translating mundane, mass-produced forms? How does stained glass, in your view, change or deepen the viewer’s relationship to objects that might otherwise be overlooked?

I’m attracted to glass as a material for a myriad of reasons from practical to conceptual. I love its inherent qualities: from the high level of fabrication it starts at when buying it in sheets, its like a lot of the labor has already been done for me before I even begin, its ability to shift in color and appearance throughout different lighting conditions which is a great lead in to playing with ideas of perception. I love that the material is color and in that way it feels like a pure form of sculpture where I get to manipulate and build with color vs dealing with surface treatments. I love its ability to endure and it’s stability; glass can exist outside, rain or shine, without its color fading over time from light or being weathered by the water. I also appreciate the associations it has, the reverence that comes with stained glass due to its historical use in churches, the suggested fragility of it, etc. Most of all I love experimenting with the medium and partaking in collective knowledge of other glass artists that are very generous in sharing their discoveries online.

Hanging Over Me (detail), 2023. Glass, lead, aluminum, steel. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Evan Walsh

Hanging Over Me (detail), 2023. Glass, lead, aluminum, steel. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Evan Walsh

In several installations, elements such as water, light, and subtle movement play active roles. How do you think about the choreography of these environmental components, and what do they allow you to express as a sculptor?

Since I make sculpture, space and time are inherently important in my work. I mentioned the role the viewer plays in completing a piece and in a similar way I consider time, light and change as important players in a work. A work which shifts over time, like the accumulation of coins in the fountain piece Fade to Black or the “Tender” bucket revealing a poem in the penny press piece Wistful Thinking as coins are used up, means viewers will have different experiences of the work depending on when they encounter it. I like the idea that to get the full experience you might have to go view the work multiple times. Perception is a personal thing, and I think these shifting elements help to highlight that.

I wish I could remember these dreams what what they're trying to tell me, 2021. Wood, ceramic, resin, metal, paint. Photo: Josh Schaedel

As your projects have grown in scale and complexity, what logistical challenges or discoveries have shaped your recent work? How have these practical experiences influenced the way you think about production and exhibition-making?

A challenge for me has been finding ways to make the large-scale installations I’m interested in making while accommodating the reality that there isn’t really a market for that kind of work. My attempt to adapt have been to make multiple pieces that can conceptually stand-alone while also coming together to create an installation with a larger narrative. I’m working on a show right now that deals with this issue at a scale that’s new to me and I’m really excited to see it realized.

I wish I could remember these dreams what what they're trying to tell me, 2021. Wood, ceramic, resin, metal, paint. Photo: Josh Schaedel

I wish I could remember these dreams what what they're trying to tell me, 2021. Wood, ceramic, resin, metal, paint. Photo: Josh Schaedel

The idea of “here” has become central to your recent exhibitions, both as a literal location and as a shifting psychological condition. How do you approach the tension between geographical place and internal sense of place in your work?

The idea of “here” is great because its universally understood while being totally meaningless without context, and because of that “here”, like perception, is something that shifts and continuously changes. Navigating geographical place vs sense of place is a bit of a dance in my work, and I’m always trying to strike the right balance between vagueness and specificity to hit both those chords at once. I try and use signs that can be both broad and direct to create an experience that is simultaneous; something that feels familiar but also abstract depending on how you look at it. I think the use of pun, language play and double meaning helps a lot with that in my work.

Looking ahead, what upcoming directions or projects are you most excited to pursue, whether in the studio or beyond?

I’m working on a cite-specific solo show right now. In it, I’m using new glass techniques I started working with in the postcard pieces that are in Made in LA and it’s been exciting to push myself to develop this process more. It’s a big project so I’m just going full studio rat mode right now and am excited to see what comes out.

To learn more about Kelly Wall visit her Instagram and website